Most SaaS products start with a single onboarding tour that walks new users through the interface. This works when the product is simple and every user follows the same path. But as the product grows—more features, more user types, more workflows—that linear tour becomes a liability. Users who don't need a feature right now skip through it. Users who do need help can't find it three weeks later when they finally encounter that workflow. Support tickets pile up around predictable friction points that the tour never addressed because it fired too early.

The TL;DR

-

Contextual in-app guidance triggers based on user actions and current workflow context, achieving 72% completion rates for three-step tours, while static product tours often get dismissed or ignored.

-

Product tours fail because they fire too early (at signup) and can't adapt to when users actually need help—82% of users expect onboarding tailored to their specific role and goals.

-

Contextual guidance uses event-based triggers, user segmentation, frequency caps, and per-user state management to deliver help at the exact moment it's needed without creating notification fatigue.

-

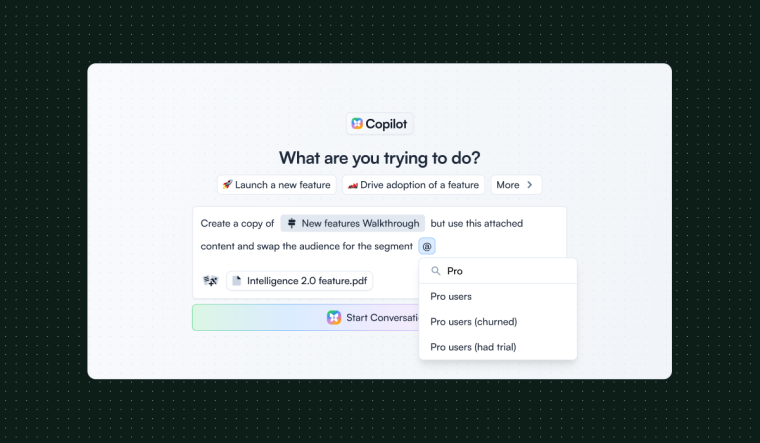

Chameleon enables teams to create contextual guidance with visual editing, event-based targeting, and segmentation—allowing product and growth teams to iterate without engineering dependencies.

-

Best practices include instrumenting meaningful workflow events, segmenting by user context (role, plan, behavior), using aggressive frequency caps, and measuring whether guidance actually improves task completion rates.

The operational problem is timing and relevance. A tour triggered at signup can't anticipate what a user will struggle with on day seven or day thirty. It can't adapt to whether someone is an admin setting up integrations or an end user trying to complete their first task. It can't distinguish between a user who has already figured something out and one who is stuck. The result is guidance that feels intrusive to experienced users and absent to users who actually need it.

This problem becomes acute as teams scale. The gap between what users need and what static tours deliver widens with every new feature, role, or workflow. Product and growth teams see activation metrics stall. Customer success teams field repetitive questions about tasks that should be self-serve. Enablement teams spend cycles updating tours that break every time the UI changes. The mismatch between one-size-fits-all guidance and real user behavior creates friction that compounds over time.

Why Static Tours Stop Working

A product tour is a sequence. It assumes users will encounter features in a specific order and need help with all of them at once. This assumption breaks down quickly. A user might skip a feature during onboarding because they don't have the data to use it yet. Three weeks later, they try to use it, get stuck, and have no idea where to find help. The tour already fired. It won't fire again. The user either figures it out through trial and error, asks support, or gives up.

The other failure mode is over-notification. Tours that fire on every login or every page load train users to dismiss them reflexively. Tooltips that appear every time a user hovers over a button become noise. In fact, 80% of users uninstall apps they don't understand how to use. Modals that interrupt workflows to explain features the user already understands create frustration. The guidance stops being helpful and starts being something users actively avoid.

The underlying issue is that static tours don't have context. They don't know what the user is trying to do right now. They don't know whether the user has already completed a task or dismissed the same tip five times. They don't know whether the user has the permissions or plan entitlements to use a feature. Without that context, guidance becomes a blunt instrument that either fires too often or not at all.

Who Feels This Problem Most

End users experience this as a gap between needing help and finding it. New users get overwhelmed by tours that explain everything at once. Returning users can't find guidance when they finally need a feature they skipped during onboarding. Power users get annoyed by tips that keep reappearing for tasks they've already mastered. The product feels harder to use than it should be, not because the workflows are complex, but because help isn't available at the right moment.

Product managers and growth teams see this in activation and adoption metrics. Users sign up, complete the initial tour, and then drop off before reaching key workflows. Feature adoption stays low even after launches because users don't discover or understand how to use new capabilities—with core features averaging just 24.5% adoption across B2B companies. Time-to-first-value stretches out because users get stuck on predictable steps that could be guided but aren't. The team knows where users struggle—analytics show the drop-off points—but static tours can't target those moments effectively.

Customer success and support teams handle the downstream cost. Tickets cluster around the same handful of workflows. Users ask how to do things that are technically documented but not discoverable in-product. The team writes help articles and records videos, but users don't find them when they're stuck. The guidance exists somewhere, just not in the context where it's needed. Support becomes a bottleneck for tasks that should be self-serve.

Enablement and operations teams maintain the tours and deal with the brittleness. Every UI change risks breaking a tour step. Every new feature requires updating the sequence. Every user segment needs a different version. The maintenance burden grows faster than the team's capacity to keep up. Tours become outdated, fire in the wrong places, or get turned off entirely because no one has time to fix them.

The Job Users Are Hiring Guidance to Do

The underlying job is to help users complete a specific task at the moment they're trying to do it. Not before, when they don't have context. Not after, when they've already struggled through it or given up. Right when they're on the relevant screen, attempting the workflow, and could benefit from a nudge or explanation.

This requires guidance that knows where the user is, what they're doing, and whether they've done it before—with 82% of users expecting onboarding tailored to their specific role and goals. It needs to appear only when relevant and disappear once it's no longer needed. It needs to adapt to differences between users—role, plan, permissions, proficiency—so that help is targeted rather than generic. And it needs to be maintainable, so teams can iterate on what works without rebuilding the entire system every time the product changes.

How Teams Approach Contextual Guidance

Teams solving this problem take different paths, depending on their engineering capacity, product complexity, and how often guidance needs to change.

Some teams build custom in-product guidance directly into the application code. This gives full control over triggers, content, and styling. Engineers can tie guidance to the exact events and conditions that matter: user actions, feature flags, API responses, UI state. This approach works well when guidance is tightly coupled to specific workflows and doesn't change often. The downside is that every update requires engineering work. Product or growth teams can't iterate on messaging, targeting, or timing without going through the development cycle. This creates a bottleneck when teams want to test different approaches or respond quickly to user feedback. It also means guidance logic lives in the codebase, which can become brittle as the product evolves.

Other teams use general-purpose analytics or feature flagging tools to trigger guidance. They instrument events for key actions—clicked this button, completed this step, encountered this error—and use those signals to show or hide UI elements. This works when the team already has robust event tracking and the engineering team is comfortable managing guidance as part of the product logic. The challenge is that these tools aren't purpose-built for guidance workflows. Managing state across sessions, handling frequency caps, segmenting by user attributes, and measuring completion all require custom implementation. Teams end up building a guidance system on top of infrastructure designed for something else. It's flexible but requires ongoing engineering effort to maintain.

A third approach is to use a dedicated in-app onboarding or product adoption tool. These platforms are built specifically for contextual guidance. They provide event-based and context-based triggering: show a tooltip when a user lands on a specific page, clicks a certain element, or meets eligibility criteria. They handle per-user state, so guidance can be shown once, suppressed after dismissal, or hidden after a user completes a task. They offer segmentation by role, plan, usage history, or custom attributes. And they include patterns like tooltips, modals, checklists, and inline hints that product and growth teams can configure without writing code. The trade-off is that these tools add another dependency and cost. They work best when guidance needs to change frequently, when non-engineering teams need to own iteration, and when the product has enough complexity that maintaining custom guidance in-code becomes a drag on velocity.

Some teams combine approaches, building critical, stable guidance into the product and using a tool for experimental or frequently changing guidance. This balances control with iteration speed, but it creates coordination overhead. Code-based guidance can drift out of sync with tool-based guidance. Ownership becomes unclear. Users sometimes see conflicting tips. The maintenance burden can double instead of halving if the team doesn't establish clear boundaries about what lives where and who maintains each type.

Patterns That Make Contextual Guidance Work

Teams that successfully improve guidance share a few common patterns. They instrument workflows with meaningful events. This doesn't mean tracking every click. It means identifying the moments where users get stuck or miss something important and making those moments detectable. Completed a setup step. Encountered an error. Landed on a page for the first time. Returned to a feature after a gap. These signals let guidance respond to what's actually happening rather than guessing based on time since signup.

The reality is messier than a one-time instrumentation effort. Event schemas drift as the product evolves. Product ships features faster than analytics can instrument them properly. Cross-team coordination on event naming breaks down. The analytics engineering tax of maintaining clean event taxonomies is real and ongoing. Teams that handle this well treat instrumentation as a continuous investment, not a setup task.

They segment guidance by user context. New users see different tips than returning users. Admins see setup guidance that end users don't. Users on plans without a feature don't see prompts to use it. Users who have already completed a task don't see reminders to do it again. This requires storing and checking user attributes and state, but it's what makes guidance feel relevant instead of repetitive.

They use frequency and suppression controls aggressively. Guidance that could be helpful once becomes annoying if it reappears every session. Teams that do this well show tips once by default, add cooldown periods between repeated guidance, and suppress tips permanently after a user dismisses them or completes the task. They treat user attention as a limited resource and spend it carefully.

They measure whether guidance actually helps. This means tracking not just whether users saw or dismissed a tip, but whether they completed the task it was meant to help with. Did users who saw the tooltip finish the workflow more often than users who didn't? Did time-to-completion improve? Did support tickets about that workflow decrease?

The measurement challenge is harder than it looks. Selection bias matters: users who see guidance may already be more engaged than those who don't. Confounding variables complicate attribution when guidance ships alongside other changes. Sample sizes for specific workflows are often too small for statistical confidence. Impact often shows up weeks later in retention rather than immediately in completion rates. Teams that iterate effectively use these signals directionally, not as precise proof, and look for consistent patterns across multiple workflows rather than relying on single experiments.

When Contextual Guidance Isn't the Right Solution

This approach doesn't make sense for every product or team. If the product is simple enough that most users figure it out without help, adding guidance creates complexity without much benefit. If the core problem is that the product itself is confusing or poorly designed, guidance becomes a band-aid over a deeper UX issue. Fixing the interface is usually better than explaining a bad interface.

Once you start adding guidance, it can become a crutch. Product teams ship confusing UI and add a tooltip instead of fixing the underlying design problem. This creates guidance debt that accumulates over time and actively prevents necessary UX improvements. Teams need to be honest about whether they're solving a workflow complexity problem or papering over poor design decisions.

If the team can't instrument meaningful events or store per-user state, contextual guidance is hard to implement well. Without reliable signals about what users are doing, triggers become guesswork. Without state management, guidance either fires too often or not at all. Teams in this position are better off focusing on improving analytics and user data infrastructure before layering on guidance.

If the UI changes constantly and the team doesn't have capacity to maintain guidance, it will break and become a source of user frustration rather than help. Guidance that points to elements that no longer exist or explains workflows that have changed is worse than no guidance. Teams need to be realistic about their ability to keep guidance current.

If the product has very few users or is still in early validation stages, building or buying guidance infrastructure is premature. The priority is figuring out product-market fit, not optimizing onboarding flows. Manual onboarding, support-driven help, and direct user feedback are usually more valuable at that stage. You also face a cold start problem: you need usage data to know where to add guidance, but you need guidance to get users to the point where they generate meaningful usage data. Early-stage products are better off with direct user contact to understand friction points.

Where Dedicated Tools Fit

A dedicated in-app onboarding or product adoption tool makes sense when guidance needs to change frequently and non-engineering teams need to own that iteration. Product managers, growth leads, or customer success teams can update targeting, content, and triggers without waiting for engineering cycles. This speeds up experimentation and lets teams respond quickly to user feedback or product changes.

These tools are most valuable for teams with complex products where users follow different paths based on role, plan, or use case. The segmentation, state management, and pattern libraries these platforms provide would otherwise require significant custom development. They're also useful when the team wants to run structured experiments on guidance and measure impact through analytics integrations.

The build versus buy decision comes down to opportunity cost and maintenance burden. A tool might cost $20K-50K annually depending on user volume. Building in-house means ongoing engineering maintenance, design debt, and the risk you build something that works for today's product but doesn't scale. The real cost of building is the opportunity cost: engineering time that could go toward core product work. Teams should evaluate whether they have the sustained capacity to maintain a custom solution as the product evolves, not just whether they can build the initial version.

What these tools don't replace is product analytics, feature flagging, or customer data infrastructure. They consume signals from those systems—events, user attributes, feature entitlements—but they don't generate them. Teams still need to instrument their product and maintain clean user data. The tool makes it easier to act on that data to deliver guidance, but it doesn't solve the underlying instrumentation problem.

They also don't replace good product design or clear UI. Guidance helps users navigate complexity, but it shouldn't be the primary way users understand the product. If users can't complete basic tasks without constant prompting, the product needs design work, not more tooltips.

Tools in this category include platforms like Chameleon, Appcues, Pendo, and Userpilot. They provide similar core capabilities around event-based targeting, user segmentation, and in-app patterns, with differences in pricing models, integration depth, and how they handle versioning when you ship breaking UI changes. Evaluating these tools requires understanding your integration maintenance burden and whether the platform creates technical debt as your product evolves.

Who Owns This

The organizational question matters as much as the technical one. In most companies, contextual guidance falls into a gap between teams. Product owns the roadmap but may not have bandwidth for guidance iteration. Growth owns activation metrics but may lack context on technical constraints. Customer success sees where users struggle but doesn't have design resources. Engineering can build it but shouldn't own content decisions.

The teams that make this work establish clear ownership. Someone owns the guidance strategy: which workflows get help, what the success metrics are, how guidance fits into the broader product experience. Someone owns execution: creating content, configuring targeting, running experiments. Someone owns maintenance: keeping guidance current as the product changes, deprecating outdated tips, monitoring for broken experiences.

The promise that non-engineering teams can iterate independently often fails without this clarity. Those teams need design support for content, technical context for targeting decisions, and analytics access for measurement. The tool removes the engineering bottleneck for changes, but it doesn't remove the need for cross-functional coordination.

Making the Decision

If this problem feels familiar, start by identifying where users actually get stuck. Look at support tickets, session recordings, and drop-off points in key workflows. Don't try to guide everything. Pick one or two moments where guidance could clearly help users complete a task they're already trying to do.

The prioritization question is harder than it looks. Analytics might show five equally bad drop-off points. Support tickets might cluster around ten different workflows. The framework that works: prioritize workflows that are both high-impact (lots of users hit them, they're critical to activation or expansion) and high-confidence (you understand why users struggle and have a clear hypothesis for how guidance would help). Avoid the temptation to add guidance everywhere. Start with workflows where you can measure clear before-and-after improvement.

Next, assess whether you can reliably detect those moments. Do you have events that fire when users land on the relevant screen, take the action, or encounter the error? Can you check whether a user has already completed the task or dismissed guidance about it? If not, the priority is instrumentation, not guidance.

Then consider who needs to own iteration and whether you have the organizational capacity to sustain it. If guidance will change infrequently and engineering is comfortable maintaining it in-code, that might be the simplest path. If product or growth teams need to test different approaches quickly, a tool that lets them iterate without code is worth evaluating. If you're somewhere in between, think about which workflows need fast iteration and which can be stable.

The harder question is getting engineering buy-in when they're underwater on core roadmap work. The case that works: frame guidance as reducing support burden and improving activation metrics that the team already cares about. Show the cost of not doing it—support tickets, drop-off rates, time-to-value. Propose starting small with one high-impact workflow rather than a comprehensive system. If you're evaluating a tool, be clear about what engineering won't have to build or maintain.

Finally, be honest about maintenance capacity. Guidance that goes stale is worse than no guidance. If the team doesn't have bandwidth to keep it current as the product evolves, start small with one or two high-impact workflows and expand only if you can sustain it. Establish a review cadence: someone checks quarterly whether guidance still points to the right places, whether content is still accurate, whether workflows have changed enough to require updates.

The goal isn't to build a comprehensive guidance system. It's to reduce friction at specific moments where users predictably struggle. Start there, measure whether it helps, and iterate based on what you learn.

Boost Product-Led Growth 🚀

Convert users with targeted experiences, built without engineering