Most SaaS teams ship features that existing users never discover or adopt. A product manager launches a workflow automation capability, instruments the events, and three weeks later sees that only 8% of eligible users have tried it once and fewer than 3% use it regularly. Customer success hears nothing. The feature sits idle while the team debates whether to promote it harder or move on.

The TL;DR

-

Most SaaS features see only 8% first-time usage and 3% regular adoption because users don't discover them—post-launch adoption requires contextual in-app prompts, smart segmentation, and continuous measurement.

-

Effective feature adoption strategies reduce time-to-first-value with defaults and templates (increasing retention by up to 50%), use controlled rollouts to test impact, and measure adoption as a multi-stage funnel.

-

Prioritize adoption work for features tied to expansion revenue, retention, or strategic differentiation—not every feature deserves deep adoption investment, especially table-stakes capabilities.

-

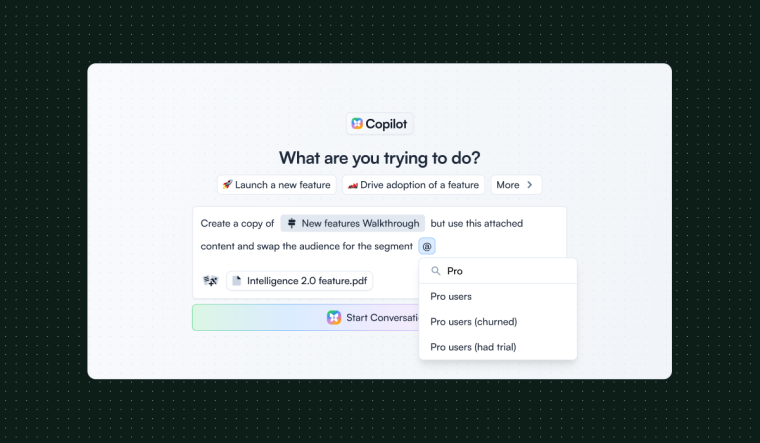

Chameleon helps teams move faster on discovery and guidance by enabling non-technical teams to create contextual prompts, test different messaging, and iterate based on adoption data without code changes.

-

Track adoption funnel stages: exposure → awareness → first use → activation → repeat use. Each drop-off point indicates different fixes—discovery issues need better prompts, activation problems need reduced friction.

This isn't a launch problem. It's an adoption problem. The feature exists, but the gap between shipping code and changing user behavior is wider than most teams expect. Users don't check release notes. They don't explore menus. They continue using the product the way they already know, and unless something interrupts that habit at exactly the right moment with exactly the right context, the new feature stays invisible.

The cost isn't just wasted engineering effort. Low adoption makes it impossible to validate whether the feature solves the problem it was designed for. Product teams cannot learn. Customer success cannot drive expansion (with only 43% of CS teams actually owning expansion revenue). Sales cannot point to new value during renewals. The feature becomes technical debt that nobody wants to remove or defend.

This problem appears predictably as SaaS companies scale. Early on, a small user base and tight feedback loops mean most customers hear about new features directly from the team. As the customer base grows, that direct communication breaks down. Different user segments have different workflows, different levels of engagement, and different reasons for using the product. A feature that is critical for one segment may be irrelevant or distracting for another. Broad announcements create noise. Targeted outreach doesn't scale. The product itself must do the work of guiding users to the right capability at the right time, but most products aren't instrumented or designed to do that well.

The underlying challenge is more than awareness. It's the combination of awareness, understanding, first-use friction, and repeat behavior. A user might see a banner about a new feature but not understand why it matters to them. They might understand the value but encounter friction during setup (missing defaults, unclear next steps, no sample data to experiment with) and abandon it. They might complete one interaction but never return because the feature didn't deliver a quick win or fit naturally into their existing workflow. Adoption is a funnel, and most features leak users at every stage.

Teams that solve this problem well treat post-launch adoption as a distinct workstream with clear ownership, instrumentation, and iteration cycles. They don't assume that shipping the feature is enough. They build discovery, guidance, and feedback mechanisms into the product experience itself. They measure adoption as a multi-stage funnel and iterate based on where users drop off. They also recognize that not all features deserve the same adoption effort. Some are table-stakes capabilities that a small segment will find on their own. Others are strategic differentiators that require deliberate, sustained effort to drive usage and prove value.

The harder question is which features warrant that investment. If you're shipping two or three features per month, you cannot do deep adoption work on all of them. The features tied to expansion, retention, or strategic differentiation get priority. Features that validate a new market or user segment get priority. Table-stakes features that fill gaps but don't drive growth can launch with minimal adoption support. The decision depends on what you're trying to learn and what business outcome you're trying to move.

How Teams Approach This Problem

There are several ways to increase feature adoption after launch. The right approach depends on the feature's complexity, the user segments it serves, how much friction exists during first use, and whether the team can measure and iterate quickly. Most teams end up combining multiple approaches, but the starting point matters because it determines who owns the work, how fast you can learn, and where bottlenecks appear.

Contextual In-Product Prompts and Guidance

The most direct approach is to surface the feature inside the product at the moment it becomes relevant. This might be a tooltip that appears when a user hovers near the new capability, a banner that shows up in a specific workflow, a checklist that guides users through setup, or an empty state that explains what the feature does and offers a clear next step. The goal is to make discovery just-in-time rather than requiring users to remember an email or seek out documentation.

This works well when the feature is tied to a specific user action or workflow. If you launch a new reporting capability, you can prompt users when they navigate to the analytics section. If you add a collaboration feature, you can surface it when a user invites a teammate. The prompt is contextual, the value is clear, and the user is already in the right mindset to try it.

The breakdown happens when prompts are too broad, too frequent, or too interruptive. A banner that shows up on every page for every user creates fatigue and trains people to ignore all in-product messaging. A modal that blocks the workflow to announce a feature most users don't need damages trust and increases the risk that users will dismiss future prompts without reading them. Timing and targeting matter more than volume. A single well-placed tooltip seen by the right user at the right moment will outperform a dozen generic announcements.

The real friction here is usually organizational, not technical. Engineering teams push back on tooltips and banners as UI clutter, especially if they're being asked to build one-off prompts for every feature launch. The PM ends up negotiating for eng time to add "just another tooltip" while the team wants to ship the next feature. This is where the build-versus-buy decision matters. If every prompt requires engineering work and a deploy cycle, most features won't get the attention they need because the coordination cost is too high. If non-technical team members can create and update prompts without code, the bottleneck shifts from implementation to strategy. The difference in iteration speed often determines whether adoption improves or stalls.

Reducing Time-to-First-Value

Even when users discover a feature, friction during first use kills adoption. If the feature requires manual setup, asks for information the user doesn't have on hand, or fails to deliver a quick win, most users will abandon it and not return. The solution is to design the first experience to minimize effort and maximize the chance of success.

This means providing defaults instead of empty fields, offering templates instead of blank canvases, and pre-populating sample data so users can explore safely without risking their real work—approaches that can increase retention by up to 50%. Include undo or preview options so users feel confident experimenting. Break complex workflows into smaller steps with clear progress indicators. The goal is to get the user to a moment of value (something they can see, use, or share) as quickly as possible, ideally within the first session.

This approach works best for features that have inherent setup complexity or require users to invest effort before seeing results. A new dashboard builder benefits from templates. A workflow automation tool benefits from pre-built examples. A collaboration feature benefits from sample projects that demonstrate the value before asking users to invite their team.

The breakdown happens when the team optimizes for speed at the expense of real value. Defaults that don't match the user's actual needs create a false sense of progress. Sample data that feels too generic or irrelevant makes the feature seem like a toy rather than a tool. The first experience must be both fast and meaningful. If users complete the setup but don't see why the feature matters to their specific workflow, they won't come back.

This is also where adoption initiatives often stall. Design wants to research the right defaults. Engineering wants to ship and move on. Product is stuck mediating between "let's get this right" and "we need to ship the next feature." The coordination tax is real. Improving time-to-first-value usually requires product changes, not just messaging changes, which means longer iteration cycles and more cross-functional alignment. Before committing to this approach, consider whether the adoption gain justifies the cost. If the feature serves a narrow segment or isn't strategic, a simpler discovery mechanism may be enough.

Segmentation and Targeted Rollouts

Not all users should see a new feature at the same time or in the same way. A power user and a new user have different contexts, different workflows, and different tolerance for complexity. A feature that is critical for one customer segment may be distracting or confusing for another. Segmentation allows teams to control who sees the feature, when they see it, and how it is introduced.

This might mean rolling out the feature to a small cohort first: users who have shown intent signals like visiting a related page, users in a specific role or account tier, or users who have explicitly requested the capability. It might mean using feature flags to enable the feature for internal users or beta customers before a broader launch. It might mean tailoring the in-product messaging based on user attributes, showing a technical walkthrough to developers and a high-level overview to business users.

This works well when the feature serves multiple audiences with different needs, when there is risk that broad exposure could hurt retention or create support load, or when the team wants to learn from a smaller group before scaling. Controlled rollouts also make it easier to measure impact. If you release to 10% of users and compare their behavior to a control group, you can see whether the feature increases engagement, decreases churn, or has no effect.

The breakdown happens when segmentation becomes an excuse to avoid broader adoption. A feature that stays in beta for months because the team is afraid of negative feedback isn't being adopted. It's being hidden. Segmentation is a tool for learning and iteration, not a permanent state. The other risk is over-segmentation. If the targeting rules are too complex or too narrow, the feature never reaches enough users to validate whether it works. The goal is to start narrow, learn fast, and expand deliberately.

Segmentation also surfaces cross-functional tension. Sales wants to demo the feature to prospects. Customer success wants to drive adoption for expansion. Product wants to validate the hypothesis with a controlled rollout. These goals often conflict. A feature that CS is pushing to drive upsells may not be ready for broad adoption. A feature that Sales is demoing may create support load if it reaches users who aren't ready for it. Deciding who owns the adoption target and how to balance these competing pressures is as important as the technical implementation.

The ability to target and measure independently often determines whether a feature iterates toward strong adoption or launches once and stagnates. If feature flags and user segmentation are built into the product, product managers can control rollouts without engineering help. If not, every change requires code and deploys, which slows learning.

Measurement and Iteration

Adoption isn't a single event. It's a funnel that moves from exposure to awareness to first use to repeat use. Most teams measure only the top or bottom of that funnel (how many users saw an announcement, or how many users have ever triggered the feature) but the real insights come from understanding where users drop off and why.

Define each stage clearly. Exposure means the user was eligible and the feature was available to them. Awareness means they saw a prompt, message, or UI element that explained the feature. First use means they took the initial action: clicked a button, completed a setup step, created their first instance. Activation means they reached a meaningful outcome, not just a click. Repeat use means they came back and used the feature again, which is the strongest signal that it delivered value.

Measuring this funnel makes it possible to diagnose problems. If users are exposed but not aware, the discovery mechanism isn't working. If they are aware but not trying the feature, the value proposition is unclear or the friction is too high. If they try it once but don't come back, the first experience didn't deliver a quick win or the feature doesn't fit their workflow. Each stage suggests a different fix.

This works well when the team has clear instrumentation, can run A/B tests or controlled experiments, and has the ability to iterate quickly based on data. It also requires defining success metrics and guardrail metrics up front. Success metrics measure adoption and value: activation rate, repeat usage, time-to-first-value. Guardrail metrics measure risk: retention, churn, support tickets, user sentiment. A feature that increases activation but also increases churn isn't succeeding.

The problem is that most teams are dealing with instrumentation debt. Events weren't set up correctly at launch. Analytics is a mess. It takes three sprints to get clean data. The section above assumes measurement infrastructure exists, but if you're reading this because adoption is low, there's a good chance your instrumentation is incomplete. Before investing heavily in adoption tactics, confirm you can actually measure the funnel. If you can't, the first step is fixing the data pipeline, not optimizing messaging.

The breakdown also happens when measurement is too slow, too manual, or too disconnected from action. If it takes two weeks to pull a report and another two weeks to ship a change, the team cannot learn fast enough. If the data lives in a dashboard that no one checks, it doesn't drive decisions. If there's no clear owner responsible for monitoring the funnel and running experiments, adoption becomes a launch-and-forget problem.

Where Chameleon Fits

Chameleon helps teams move faster on the discovery and guidance side of this problem. If your bottleneck is engineering time for tooltips, banners, and checklists, or if you need to test different messaging and targeting without code changes, a tool like Chameleon can shift ownership to product and growth teams. It's most useful for mid-stage and growth-stage companies shipping features regularly and iterating on adoption. It's less relevant if you're very early stage, if you've already built robust in-house systems, or if your adoption problem is fundamentally about product design rather than awareness and friction. Book a demo to see if it fits your workflow.

When This Approach Is Not the Right Solution

Driving post-launch adoption only works if the feature itself is sound. If the feature doesn't solve a real problem, if the value proposition is unclear, or if the design is fundamentally flawed, no amount of prompting, guidance, or measurement will fix it. Adoption tactics assume the feature has potential value and the main blockers are awareness and friction. If the feature is mis-scoped or the product-market fit is weak, the right move is to revisit the feature itself, not to optimize the rollout.

This approach also doesn't work if the team cannot measure adoption reliably. If events aren't instrumented, if there's no way to identify which users are eligible for the feature, or if the data pipeline is too slow to support iteration, the team is flying blind. Adoption efforts require a feedback loop. Without clear metrics on exposure, activation, and repeat use, it's impossible to know what is working or where to focus next.

It's also not the right solution if the team doesn't have the capacity or authority to iterate. If every change requires a long approval process, if there's no clear owner responsible for adoption, or if the team ships the feature and immediately moves on to the next project, adoption will stall. Post-launch adoption isn't a one-time campaign. It's an ongoing process of learning, testing, and refining. Teams that treat it as a launch checklist item rather than a continuous workstream won't see results.

Sometimes the right decision is to let a feature sit at low adoption and move on. If the feature fills a gap but isn't strategic, if it serves a narrow segment that will find it on their own, or if the opportunity cost of optimization is too high, accept the current adoption rate and ship the next thing. Not every feature deserves deep adoption work. The question is whether low adoption is blocking something important: validation of a hypothesis, expansion revenue, retention, or strategic differentiation. If it's not blocking any of those, the feature may be fine as-is.

There's also the feature graveyard decision. At some point, a feature with persistently low adoption becomes technical debt. If you've tried multiple adoption approaches, if the feature isn't strategic, and if maintaining it creates drag on the codebase or the product experience, consider deprecating it. The signal is usually a combination of low usage, high maintenance cost, and lack of strategic value. Sunsetting a feature is often the right move, but most teams avoid it because no one wants to admit the investment didn't pay off.

Finally, this approach is less relevant for features that are inherently low-frequency or serve a very narrow use case. If the feature is designed for a small segment of power users who will seek it out on their own, aggressive prompting may do more harm than good. If the feature is something users need only occasionally (like an export function or an admin setting), trying to drive repeat usage doesn't make sense. The goal is adoption that creates value, not adoption for its own sake.

Thinking Through Next Steps

If low feature adoption is blocking your ability to validate new work, expand customer value, or justify continued investment in product development, the first step is to pick one recent feature and map its adoption funnel. Identify how many users were eligible, how many were exposed to any kind of announcement or prompt, how many tried it, how many reached a meaningful outcome, and how many used it again. This will show you where the biggest drop-off is happening.

Look at where users are falling out of the funnel. If most eligible users never become aware of the feature, the problem is discovery. Users don't know the feature exists or don't understand when it's relevant to them. The fix is better in-product prompts, contextual messaging, or more targeted communication.

If users see the feature but don't try it, the problem is either unclear value or high perceived effort. They see the feature but don't believe it's worth trying, or they start the process and abandon it because it feels too complex. The fix is clearer messaging about outcomes, better empty states, or reducing the friction in the first experience.

If users try the feature once but don't come back, the feature didn't deliver a quick win or doesn't fit naturally into their workflow. The fix is improving the first-run experience, providing better defaults or templates, or revisiting whether the feature solves the problem it was designed for.

If the funnel is broken at multiple stages, prioritize the leak that affects the most users or the leak that's easiest to fix. If 70% of users never become aware and 50% of aware users don't try it, start with discovery. If awareness is high but activation is low, start with first-use friction. Don't try to fix everything at once.

Once you know where the funnel is breaking, decide whether you can iterate quickly enough to fix it. If every change requires engineering work and a deploy cycle, and your team is already stretched thin, you'll struggle to improve adoption at the pace needed to learn. If you can run experiments, update messaging, and test new approaches without code changes, you have a better chance of finding what works.

The harder question is whether fixing this feature is the right use of time. If you have no bandwidth to iterate, if the feature isn't strategic, or if the opportunity cost is too high, it may be better to accept the current adoption rate and move on. The goal isn't to drive adoption for every feature. The goal is to make sure that the features you invest in (especially the ones that are strategic, differentiated, or tied to expansion and retention) actually get used and deliver value. If you can't measure that or iterate on it, the problem isn't the feature. It's the system around it.

Boost Product-Led Growth 🚀

Convert users with targeted experiences, built without engineering